The global shortage of semiconductors remains widespread as supply chain disruptions continue to hinder the chip manufacturing recovery following the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. This report examines the major supply chain events that have impacted the semiconductor industry during the first half of 2022 and explores what automotive companies can do to manage rising chip prices and prolonged supply shortages.

To the contrary of more optimistic assessments that the worst may be over, the semiconductor shortage has the potential to further disrupt automotive supply chains and financial bottom lines through 2022 and into 2023.

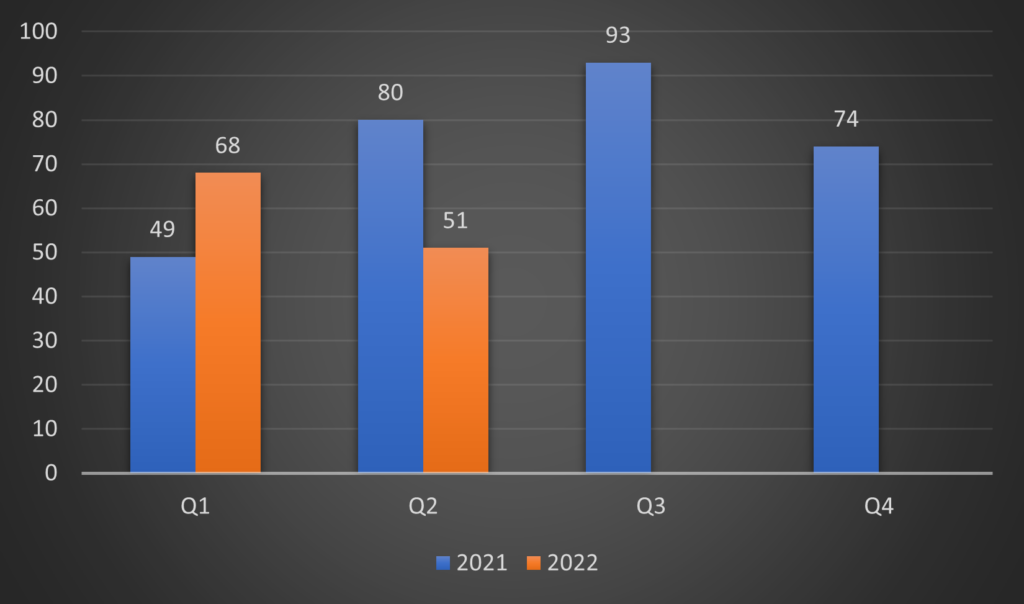

Figure 1: Recorded number of factory shutdowns due to semiconductor shortages from January 1, 2021 – June 16, 2022 (source: Everstream Analytics).

Semiconductor chip demand remains high

Semiconductor chips are essential components used in automotive products ranging from simple headlamp switches to complex fuel management systems. OEMs have been reporting extensive production stoppages since late 2020, when the pandemic and other global events began to seriously disrupt chip factory output. Global events like the Russia-Ukraine war and China’s COVID-19 lockdowns have further hampered chip manufacturing recovery, with proprietary data from Everstream Analytics revealing that more companies reported semiconductor-related production disruptions during the first quarter of 2022 than during the same period in 2021.

Semiconductor chips are advanced electronic switches that are produced along a highly differentiated supply chain. The first step in the semiconductor manufacturing process is highly research-intensive and involves designing the overall electronic layout of the chip. The design is then sent to front-end semiconductor manufacturers for fabrication where the circuit design of the chip is drawn onto silicon wafers.

![]()

Figure 2: The semiconductor supply chain (source: The Visual Capitalist).

The front-end manufacturing process is also known as wafer fabrication during which patterns of circuits are projected and eroded out on wafers that are sliced from silicon bars through a complex process of photoresist coating, lithography, etching, and ionization. Semiconductor companies that specialize in the front-end wafer fabrication process but do not design chips themselves are referred to as semiconductor fabricators or ‘fabs.’ The fabricated chips are finally sent to back-end manufacturers which test and assemble the chips into integrated circuit boards before packaging them for use further down the supply chain.

China’s zero-COVID strategy challenges semiconductor supply chains

China is currently the third largest supplier of wafer producers in the world following South Korea and Taiwan. At the end of 2021, the nation processed 3.5 million 200mm-equivalent wafers monthly, accounting for 16% of the global wafer capacity of 21.6 million. However, as Beijing continues to adhere to the zero-COVID strategy, the lockdowns scattering the nation have further disrupted semiconductor supply chains.

Some manufacturers attempted to maintain their full capacity by implementing closed-loop management. However, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), China’s top chip maker, predicted a 5% reduction in its production in the second quarter despite the claimed full operation in Shanghai. Similarly, Microchip Technology Inc., a producer of microcontrollers, and integrated circuits, reported that a large part of its products were unavailable due to key suppliers located in the Shanghai area having shut down production, and the company not having buffer stock.

Impacts of reduced output together with crippled shipments during the lockdown continue to ripple through automotive supply chains. Even though car makers including BMW and Mercedes-Benz signaled a temporary easing of the semiconductor shortage in early June 2022, there are signs that the industry is unlikely to receive sufficient supply in the coming months. Because of a lack of semiconductor supply, Toyota Motor Corporation has had to adjust production at 16 lines of 10 factories since May 25, cutting the June output plan by 100,000 units. Stellantis N.V. also continues to experience a shortage of semiconductors, with some of its plants in Mexico, Canada, and Italy having suspended operations in early June.

Neon gas shortage could impact medium-term semiconductor output

Another major disruption to semiconductor manufacturing in 2022 involves an ongoing shortage of neon gas which emerged because of the Russia-Ukraine outbreak of war in late February. Neon gas is a vital part of the wafer fabrication process and global neon usage for chip production reached 540,000 metric tons in 2021. The gas is utilized as a medium during lithography when chip designs are etched onto silicon wafers. Russia and Ukraine were both major producers of neon gas prior to the war due to their strong steel industries, with noble gases often being produced as a by-product.

Prior to the beginning of the conflict, two Ukrainian companies – Ingas LLC in Mariupol and Cryoin LLC in Odesa – produced around 25% of global neon supply and 45 – 55% of all semiconductor-grade neon globally. Both companies have halted production indefinitely and are expected to face significant challenges in restarting production as heavy damage to Ukrainian infrastructure in Mariupol and Odesa means that both companies will face significant logistical challenges. The war also suspended global access to the Russian neon market following a June 2 decision by Russian authorities to restrict the export of noble gases in retaliation for Western sanctions on semiconductor exports to Russia.

A neon shortage is unlikely to cause short term production disruptions for semiconductor manufacturers as most major firms have taken steps to reduce their reliance on neon from Ukraine after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 caused a nearly 600% spike in neon prices. The ongoing crisis should have minimal impact on short term semiconductor production schedules as many major chipmakers including TSMC, Intel, Samsung, and SK Hynix have two to three months of neon supply stockpiled while around six months of neon supply remain within the neon gas market.

Despite this short-term stability, semiconductor manufacturers could face longer term disruptions if they are unable to secure alternate sources of neon before the market runs out of existing supplies. China is emerging as the most likely alternative source to Ukrainian neon supply due to its strong steel industry and an existing presence of foreign-based gas manufacturers and major local gas producers. However, companies that pivot to China for their neon supply could find themselves open to other supply chain risks, including sudden production disruptions from COVID-19 lockdowns and other geopolitical risks that could arise over China’s support for Russia in the ongoing conflict.

Unforeseen risks hinder chip recovery in East Asia

In the first two quarters of 2022, semiconductor manufacturers in Asia had to deal with several unforeseen disturbances.

A week-long strike by truck drivers in South Korea disrupted shipments to China of isopropyl alcohol, a key cleaning agent used by makers of semiconductor chips, while leading photolithography systems maker ASML recently warned of a shortage of lenses that will impede its ability to increase production output to chip makers around the world, including TSMC, Samsung, and Intel.

Around seven exabytes of flash memory storage was lost following contamination at two Japanese plants of Western Digital and Kioxia in late February. The memory chip manufacturer suspended production at the two facilities after the incident. Full capacity was not expected to be reached until June.

Chip output in Taiwan and Japan remains vulnerable to natural disasters including earthquakes. Semiconductor companies remain highly vulnerable to earthquake-related production disruptions due to the usage of clean rooms as well as high precision equipment like lasers and image sensors in the fabrication process. A 7.4 magnitude earthquake on March 16 in Japan caused notable production disruptions to two of Renesas Corporation’s front-end semiconductor plants in Hitachinaka and Taskaki, which reportedly took 10 and 6 days respectively to return to full production.

Equipment shortage could prolong chip supply crunch into 2023

In the second half of 2022, the demand for consumer electronics is expected to drop as consumption has begun to shift from goods to services in the post-pandemic era, with inflation potentially causing further concerns on the consumer side. The drop in demand could ease the semiconductor shortage, with days of inventory increasing to 53 days in the first quarter of 2022, up from 42 days at the end of 2021.

However, while Daimler Truck, which was part of Daimler AG until December 2021, reported positive signs of pushing past the global chip shortage in early June, Toyota has cut production output in June due to the ongoing chip shortage, with its major suppliers temporarily furloughing employees. In addition, TSMC, the world’s largest semiconductor foundry based in Taiwan, warned customers that the company might not be able to increase production as quickly as expected of its most advanced chips needed for the next-generation smartphones and data centers due until 2024.

The reason for the delayed ramp-up was said to be the shortage of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, with lead times on new orders extending in some cases two to three years due to a lack of less-advanced chips. While semiconductor companies are planning to spend $180 billion to expand production this year, breaking ground on more than 10 new chip plants globally, the inability of manufacturing equipment makers to fulfill orders is likely to delay significant output increases and an easing of the global supply shortage into 2023.

Recommendations

Build end-to-end supply chain visibility: The ripple effects of political unrests and China’s COVID-19 curbs have underlined the significance of investing in supply chain technology capable of mapping out supplier networks and providing greater end-to-end visibility. Supply chain risk management tools can provide supply chain managers with early warnings on potential disruptions, giving them a competitive advantage when deciding to shift their sourcing of raw materials and components to alternative suppliers or areas.

Develop dual-sourcing practices: Despite the lower costs generated from single-sourcing strategies, buying from multiple suppliers can be a better practice under the current unstable circumstances. Although dual sourcing may take up to 12 months to qualify new materials and suppliers, it is beneficial in the long run when it comes to unforeseen regional risks. With the diversification of the semiconductor supply chain anticipated in 2025, companies can leverage supply chain risk management software like the Everstream Discover Solution to increase visibility of their sub-tier supplier networks, analyzing whether any critical suppliers are located in high-risk areas.

Re-evaluate inventory strategies: The current supply chain woes highlight the need to re-evaluate inventory strategies. Considering chronic shortages, some large automakers have been asking their suppliers to stockpile months of chip supply as a contingency measure to increase their resilience against any future black swan events, shifting to a just-in-case model for these critical components. However, while Toyota has been largely unscathed by the chip shortage in 2021, its larger buffer stock did not shield it from having to cut production in recent months due to a lack of chips in 2022.

Get the latest automotive trends in our State of the Industry report.